Press Release 21/2011 - October 6, 2011

Did comets bring water to Earth?

Observations of Hartley 2 have revealed the first comet with water similar to that on our home planet.

Not only the impacts of asteroids, but also comets may have provided Earth with large parts of its water. This is a result of new measurements performed by ESA's space observatory Herschel that were led by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany. The researchers were able to identify 103P/Hartley 2 as the first comet who's water is characterized by a similar ratio of deuterium to hydrogen as Earth's water. Approximately one year ago, Hartley 2 had passed Earth in a distance of only 18 million kilometers thus allowing for the highly sensitive measurements (Nature, Advance Online Publication on October 5th, 2011).

Even though it sounds like a paradox, water is an immigrant on our blue planet. In the early days of our planetary system, Earth was so hot, that all volatiles such as water evaporated. Only the outer regions of our solar system beyond the orbit of Mars remained rich in water. From there, it is believed to have returned to Earth approximately 3.9 billion years ago - "on board" of asteroids, as scientists have assumed until now.

|

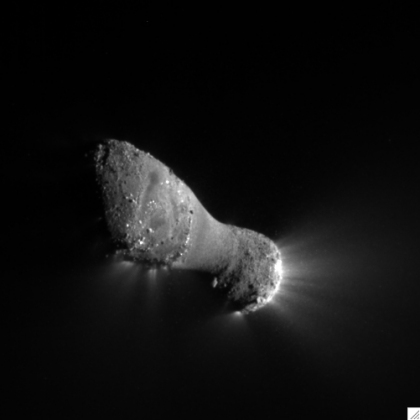

Figure 1: The water of comet 103P/Hartley 2 is characterized by a similar deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio as the water on Earth. This image of the comet was taken on November 4th, 2010, by NASA's EPOXI spacecraft.

|

(Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UMD)

|

"Current theories came to the result that less than ten percent of Earth's water originated from comets", Dr. Paul Hartogh from MPS, who led the new study, explains. "Now for the first time, our results imply, that comets may have played a much more important role", Dr. Miriam Rengel from MPS adds.

The most important clue in the search for the cosmic water supplier is deuterium, also called heavy hydrogen, which contains an additional neutron in its nucleus. On Earth, the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen is approximately 1:6400. "The small bodies that brought water to Earth should have a similar ratio of these two isotopes", explains Dr. Miguel de Val-Borro from MPS.

Until now, this held true mainly for asteroids from the outer rim of the so-called asteroid belt close to Jupiter's orbit. The six comets for which conclusions concerning this ratio have been possible so far, are likely much richer in deuterium. All these comets are believed to have originated in the vicinity of the large gas planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

Hartley 2, however, is different. Scientists believe that its cosmic home lies in the Kuiper belt, a region on the outer limits of our solar system. In October and November 2010, Hartley 2 passed Earth as closely as never before since its discovery. During this encounter, also the instruments on board the space observatory Herschel were therefore aimed at the comet. With the help of exact observations of its coma - the sheath of gas and dust surrounding comets, when they come close to the Sun - the researchers hoped to determine the deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio.

"The water molecules within the coma emit a characteristic radiation in the far infrared", says Hartogh. This also holds true for the heavier cousin of water: water moleclues in which one hydrogen atom has been replaced by a deuterium atom. "From this characteristic radiation we can determine the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen", he adds. However, since the heavy water is very rare, its radiation intensity is extremely weak. Nevertheless, with Herschel's HIFI instrument, the most sensitive detector for water vapor, the researchers were able to detect the molecule with an astonishingly good signal-to-noise ratio.

"Our measurements showed that within the comet's water there is one deuterium atom to every 6200 hydrogen atoms", says Hartogh. This ratio is very close to that on Earth. "Comets like Hartley 2 therefore have to be taken into account when looking for bodies that delivered water to Earth".

However, the new results also raise new questions. Until now, scientists assumed that the distance of a body's origin from the Sun correlated to the deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio in its water. The farther away this origin lies from the Sun, the larger this ratio should be. With a "birth place" within the Kuiper belt and thus well beyond the orbit of Neptune, Hartley 2, however, seems to violate this rule. "Either the comet originated in greater proximity to the Sun than we thought", says Hartogh. "Or the current assumptions on the distribution of deuterium have to be reconsidered". And maybe Hartley 2 is a so-called trojan that originated close to Jupiter and could never overcome its gravitational pull.

ESA's space observatory Herschel was launched on May 14th, 2009 and follows Earth's path around the Sun in a distance of 1.5 million kilometers from Earth. On board, Herschel carries three scientific instruments: the Heterodyne Instrument for the Far Infrared (HIFI), the Spectral and Photometric Imaging REceiver (SPIRE), and the Photodetector Array Camera and Spectrometer (PACS). HIFI, to which scientists from MPS contributed, is the most sensitive spectrometer ever to be developed for water observations in the far infrared. The observations reported here are part of the Herschel Guaranteed Time Key program "Water and related chemistry in the Solar System", which includes an international team of scientists led by Principal Investigator Dr. Paul Hartogh from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany.

Apart from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research also the California Institute of Technology (USA), the LESIA Observatoire de Paris (France), the Rosetta Science Operations Center (Spain), the University of Michigan (USA), and the Polish Academy of Sciences contributed to these observations.

Original Publicatioon

Paul Hartogh, Dariusz C. Lis, Dominique Bockelée-Morvan, Miguel de Val-Borro, Nicolas Biver, Michael Küppers, Martin Emprechtinger, Edwin A. Bergin, Jacques Crovisier, Miriam Rengel, Raphael Moreno, Slawomira Szutowicz und Geoffrey A. Blake:

Ocean-like water in the Jupiter-family comet 103P/Hartley 2

Natur, Advance Online Publication, October 5, 2011

Additional Information

ESA Press Release

ESA Press Release

Contakt

Dr. Birgit Krummheuer

Press and Public Relations

Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research

Max-Planck-Straße 2

37191 Katlenburg-Lindau

Tel.: 05556 979 462

Fax: 05556 979 240

Mobil: 0173 3958625

Email: krummheuer mps.mpg.de

mps.mpg.de

Dr. Paul Hartogh

Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research

Max-Planck-Straße 2

37191 Katlenburg-Lindau

Tel.: 05556 979 342

Fax: 05556 979 240

Email: hartogh mps.mpg.de

mps.mpg.de

Dr. Miriam Rengel

Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research

Max-Planck-Straße 2

37191 Katlenburg-Lindau

Tel.: 05556 979 244

Fax: 05556 979 240

Email: rengel mps.mpg.de

mps.mpg.de

Dr. Miguel de Val-Borro

Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research

Max-Planck-Straße 2

37191 Katlenburg-Lindau

Tel.: 05556 979 212

Fax: 05556 979 240

Email: deval mps.mpg.de

mps.mpg.de